Understanding Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Guide for Families and Patients

Learn about Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), a rare condition affecting the skin, brain, and eyes. Discover its symptoms, causes, and the latest treatment options to manage it effectively.

Seeing a birthmark on a newborn is common, but for some parents, it can be the first sign of a much more complex condition. If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), you likely have many questions. What exactly is this condition? How will it affect daily life? And most importantly, what can be done about it?

This article aims to answer those questions in plain, simple language. We’ll break down what Sturge-Weber syndrome is, from its genetic roots to its visible signs, and walk you through the latest treatment options. Think of this as your friendly guide to understanding the condition, so you can feel more informed and empowered when talking to your doctors.

What is Sturge-Weber Syndrome?

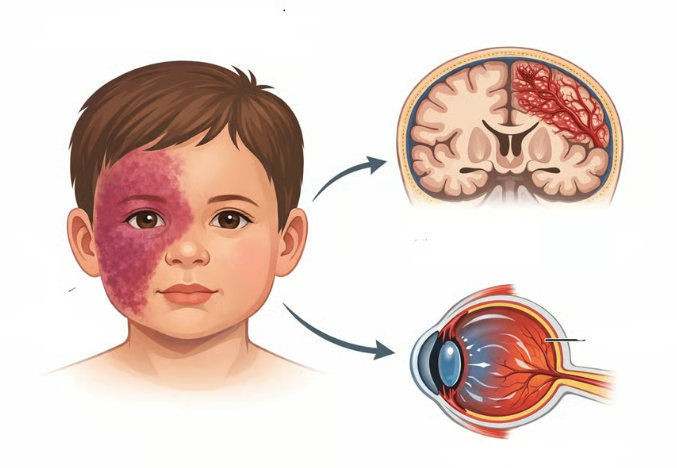

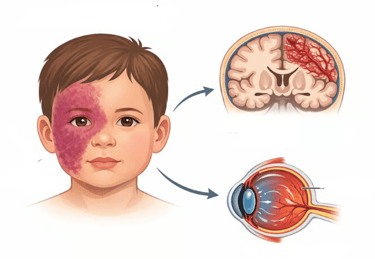

Sturge-Weber syndrome, sometimes called encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, is a rare neurological and skin condition present at birth. It’s considered a neurocutaneous disorder, a fancy term for a condition that involves both the brain (neuro) and the skin (cutaneous).

Imagine the body’s plumbing system for blood. In SWS, a tiny error during development causes some of the small blood vessels—specifically the capillaries—to form and grow abnormally. This "misplumbing" primarily affects three areas: the skin, the brain, and the eyes.

The hallmark sign is a distinctive birthmark, but the condition's impact can go much deeper, potentially causing neurological issues like seizures. SWS doesn't discriminate—it affects people of all genders and races equally and is a condition that families manage throughout their lives.

The Root Cause: A Tiny Genetic Typo

To understand what goes wrong, let's first look at how things normally work. Our bodies are made of billions of cells. Inside each cell is a control center (the nucleus) that contains our DNA—a long, instruction manual made up of genes. One of these genes is called GNAQ. Think of the GNAQ gene as a blueprint for a specific part of a faucet handle that controls water flow.

In Sturge-Weber syndrome, a spontaneous typo occurs in this blueprint after the baby is conceived. This is called a somatic mutation. It’s not something inherited from mom or dad; it happens randomly as the cells are dividing and growing. Because it happens after conception, only some of the body's cells carry the typo—specifically, the cells that go on to form the blood vessels in the skin, brain, and eyes.

This typo, most commonly known as the R183Q mutation, makes the faucet handle get stuck in the "on" position. This causes the cells lining the blood vessels to multiply too much and form abnormal, dilated vessels. This is what creates the visible birthmark on the skin and the hidden vascular malformations in the brain and eyes.

The Three Main Features of SWS

Sturge-Weber syndrome is often described by its three core features, though not every patient experiences all of them. Doctors classify SWS into different types based on which areas are affected:

Type 1: Involves both the facial birthmark and the brain malformation (and often eye issues).

Type 2: Involves the facial birthmark but no brain involvement (though eye issues can still occur).

Type 3: Involves the brain malformation but no facial birthmark (this is very rare).

The Facial Birthmark: The "Port-Wine" Stain

This is the most visible and often the first sign of SWS. At birth, it appears as a flat, pink or red mark on the skin, most commonly on the forehead and upper eyelid, usually on just one side of the face.

Why is it called a port-wine stain? Because unlike a common "stork bite" that fades, this mark persists. As the child grows, the mark grows with them, and its color can deepen to a darker red or purple, much like the color of port wine.

Think of it like this: imagine a garden hose with a kink in it. The water flow is disrupted, causing pressure to build up. In a port-wine stain, the tiny capillaries just under the skin are wider than they should be, allowing more blood to pool near the surface, which creates the reddish color.

Later in life, the skin in the birthmark area may thicken or develop small bumps. If the birthmark extends to the gums, it can cause gum overgrowth, which might lead to dental issues.

Neurological Involvement: The Brain's Challenge

The most serious aspects of SWS stem from the abnormal blood vessels on the surface of the brain, a condition called leptomeningeal angiomatosis. This affects how blood flows and drains in the brain.

Seizures/Epilepsy

This is the most common neurological symptom, affecting the vast majority of patients with brain involvement. Seizures often start in the first year of life. They happen because the abnormal blood vessels and reduced blood flow in the nearby brain tissue can irritate brain cells, causing them to fire off signals in a disorganized, chaotic way. It’s like a short circuit in the brain's electrical system.

Stroke-Like Episodes and Weakness

Children with SWS may experience sudden, temporary episodes of weakness on one side of the body (opposite the side of the birthmark), similar to a stroke. This isn't a classic stroke caused by a blocked artery, but rather a "stroke-like episode" likely triggered by seizures, reduced oxygen, or blood "sludging" in the abnormal vessels. This can lead to permanent weakness, known as hemiparesis.

Developmental and Cognitive Delays

Because of the ongoing challenges in the brain, some children may experience learning difficulties, attention issues, or developmental delays. The risk is higher for those whose seizures start very early and are hard to control. It's important to remember that the severity is highly variable. About half of individuals with SWS may have some form of intellectual disability, while others have normal intelligence.

Eye Involvement: Protecting Vision

The same abnormal blood vessels can also form in the eye, leading to increased pressure inside the eye, a condition called glaucoma.

Picture the eye like a basketball. It needs to maintain a certain amount of air pressure to keep its shape and function. In glaucoma, the eye's internal pressure becomes too high because the fluid inside can't drain properly. Over time, this high pressure can damage the optic nerve, which is like the cable connecting the eye to the brain, potentially leading to vision loss.

Glaucoma in SWS can be present at birth or develop later in childhood or even early adulthood. This is why regular eye exams are a non-negotiable part of managing SWS.

Diagnosing Sturge-Weber Syndrome

Diagnosis is usually suspected based on the presence of the facial port-wine stain, especially in the classic location on the forehead and eyelid. However, because the internal involvement isn't visible, doctors use imaging to confirm the diagnosis.

MRI with contrast: This is the best test to see the abnormal blood vessels on the surface of the brain.

CT scan: While sometimes used, MRIs are preferred as they provide more detail without radiation.

Eye exams: An ophthalmologist (eye doctor) will measure the pressure inside the eye and examine the retina to check for signs of glaucoma.

Treatment: A Team Approach to Managing Symptoms

There is no cure for Sturge-Weber syndrome, so treatment focuses on managing the symptoms and preventing complications. Because SWS affects different parts of the body, it requires a team of specialists, including neurologists, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and developmental therapists.

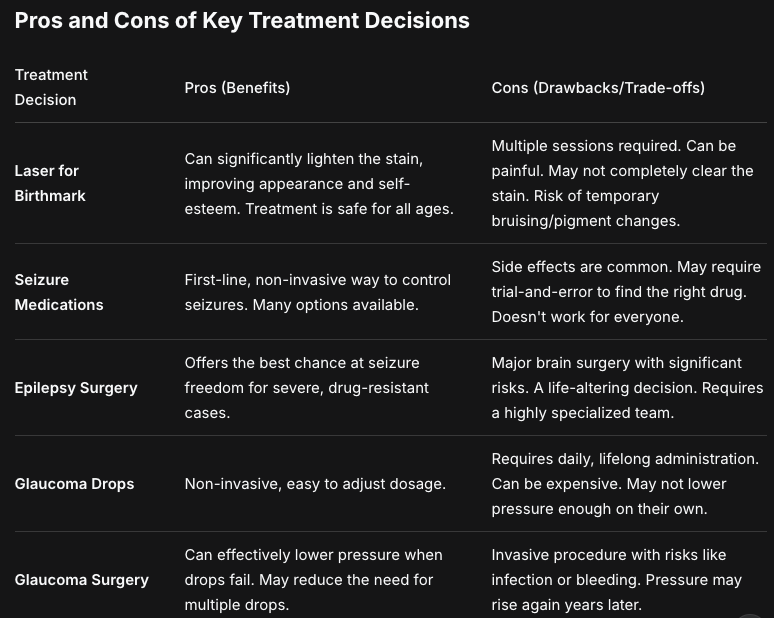

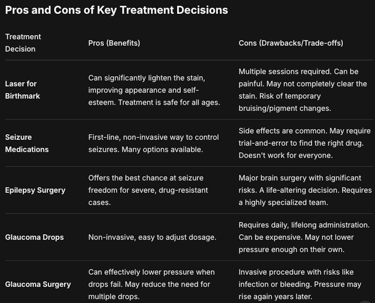

Managing the Port-Wine Stain

Treatment: Laser therapy, specifically with a pulsed dye laser, is the standard treatment. It works by targeting the hemoglobin (the protein in red blood cells) with a specific wavelength of light. The laser energy is absorbed by the blood, heating up and destroying the abnormal capillaries while leaving the surrounding skin unharmed.

Effectiveness: It can significantly lighten the stain, sometimes by 50-80%. Complete removal is rare, but most people see excellent fading. Starting treatment in infancy is often recommended because the skin is thinner and the blood vessels are smaller.

Timeline: Treatments are typically done every 4-8 weeks, and multiple sessions (often 6-10 or more) are needed to achieve the best results.

Side Effects: The procedure can be uncomfortable, often described as a rubber band snapping against the skin. Doctors use cooling devices or numbing cream to manage pain. After treatment, the area may be bruised and swollen for a week or two. There's a small risk of scarring, infection, or changes in skin color.

Who Should Consider This? Anyone who is bothered by the appearance of the birthmark. It’s a personal choice, not a medical necessity for the stain itself.

Managing Seizures

Treatment: Antiepileptic drugs are the first line of defense. Medications like levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, or valproic acid are commonly used. They work by stabilizing the electrical activity in the brain to prevent seizures.

Effectiveness: Many children achieve good seizure control with medication. However, SWS-related seizures can sometimes be difficult to manage, requiring multiple medications.

Side Effects: All seizure meds have potential side effects, which can include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, and mood changes. It's important to work closely with a neurologist to find the right medication and dosage.

If medications fail to control seizures, doctors may consider surgery. This is a major decision, usually reserved for severe cases where seizures always start from one small, well-defined area of the brain. The most common surgery is a hemispherectomy, where the affected side of the brain is disconnected from the rest, or in some cases, a focal resection to remove the seizure focus.

Managing Glaucoma

Treatment: The goal is to lower the pressure inside the eye to prevent optic nerve damage. This can be done with:

Eye Drops: These are often the first treatment. They work by either reducing the production of fluid in the eye (like beta-blockers) or helping it drain better.

Surgery: If eye drops aren't enough, surgery is needed to create a new drainage path for the fluid. Trabeculotomy and goniotomy are procedures commonly performed in children.

Effectiveness and Follow-up: Glaucoma in SWS can be very difficult to control and often requires lifelong management. Even with successful surgery, pressure can rise again years later, so regular follow-ups with an ophthalmologist are critical.

Lifestyle, Therapies, and Daily Living

Managing SWS isn't just about doctors and medications. It's about helping the individual thrive day-to-day.

Physical Therapy: Helps with weakness or motor delays, improving strength and coordination.

Occupational Therapy: Helps children master everyday skills like dressing, eating, and writing, and can also address sensory processing issues.

Speech Therapy: Essential for children with speech delays or feeding difficulties.

Educational Support: An Individualized Education Program (IEP) at school can provide crucial support for children with learning disabilities.

Habit Changes: For those with weakness, safety measures at home—like grab bars in the bathroom—can prevent falls. Wearing a medical ID bracelet is also a wise precaution for anyone with a seizure disorder.

Who Should Consider This? A Guide for Families

Seek a Specialist: If you have a child with a port-wine stain on the forehead or eyelid, you should immediately seek out a pediatric neurologist and a pediatric ophthalmologist. Early evaluation is key, even before any symptoms appear.

Consider Laser Therapy: Any individual or parent unhappy with the appearance of a port-wine stain should consult with a dermatologist or laser surgeon to discuss treatment.

Consider Epilepsy Surgery: Families of children with severe, drug-resistant seizures that significantly impact development and quality of life should discuss surgical options at a comprehensive epilepsy center.

Conclusion

Sturge-Weber syndrome is a complex and lifelong condition, but a diagnosis is not a life sentence. It is a journey, and like any journey, it's best navigated with a good map and a reliable team. The medical landscape for SWS is one of management, not cure, and the goal is always to maximize quality of life.

The key takeaway is that early and consistent intervention makes a profound difference. Regular monitoring by a team of specialists can catch and treat complications like glaucoma and seizures before they cause irreversible damage. While the challenges are real—from managing seizures to coping with a visible birthmark—so are the victories. With the right support, many individuals with SWS lead full, happy, and productive lives. The focus should always be on the person, not just the syndrome, celebrating their abilities while proactively managing their health.